This is the first installment in guest blogger Frank Klepacki’s series on music production. Today Frank looks at how evolving technology affected the development of video game music.

For the longest time, video game music had a bit of a stigma associated with it – “It’s all a bunch of bleeps and blips.” While the early days of video games – the era of the Atari 2600 – certainly represented that, people fail to realize that games outgrew that more quickly than they think.

In the mid-’80s heyday of arcades, and the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System, the music was using basic FM synthesis such as square waves and saw waves to play back a minimal 4 monophonic channels of music. Even with those limitations, though, some of the games’ music was still very cleverly composed, and remains memorable even today. The “Super Mario Brothers” themes are a prime example of this.

Traditional composers may have dismissed the idea of game music, thinking you couldn’t do all that much with it, or that it wasn’t serious. But as composers who ARE gamers, we understood that it, in fact, forced you to think harder about how you were going to utilize the technology in front of you, and make the most of it. Think about it in terms of having a snare drum, a bass, a flute, and a clarinet – and then being told to compose utilizing only those 4 players/instruments for an entire soundtrack. We accepted the challenge.

In the mid-’80s, the Amiga systems, way ahead of the curve, established sample-based sound capabilities with clever use of RAM to avoid taxing the CPU. By the late ’80s and early ’90s, the next generation of PC sound cards, such as the AdLib and Sound Blaster, became more prominent. Utilizing 11-voice FM synthesis with more customizable instrument capabilities, these sound cards allowed us to do a lot more programming of instrument changes, simulated effects and more sophisticated chord voicings to make the compositions more interesting and dynamic.

Roland also had introduced the MT-32 module, followed by the Sound Canvas, which established the “general MIDI” format, offering higher quality MIDI playback in a pro-sumer synth module that was quickly adopted by the video game industry due to its quality sound palette and ease of programmability. It was popularized in games such as “King’s Quest” and “Monkey Island.” Shortly thereafter, the next generation of consoles, such as the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, were released. Though they shared similar FM synthesis, they also introduced sample-based capabilities. Much like the Amiga, the Super Nintendo allowed use of entirely sampled instruments if you had the RAM available and cleverly allocated it, as we accomplished when I worked on the score for Disney’s “The Lion King” game.

Interestingly, as an alternative during this time, some game composers also used music trackers. Originating on the Amiga to make use of the sampled sounds with sequencing, in the ’90s we started seeing PC versions, most commonly used with Gravis Ultrasound cards, which provided robust hardware mixing that PCs lacked at the time.

During the mid-to-late ’90s sound cards continued to improve. The later Sound Blaster cards offered more sampling and playback options and higher quality sample rates, and the next-generation consoles such as the Sega Saturn and PlayStation were also able to support this. Now music could be heard the way it was composed in the pro-audio capacity, rather than be subject to the limitations of playback of earlier sound cards and consoles. Composers were able to use their synthesizers, real instruments and full band recordings if they wished, the only limitation being the budget they were given, and what sample rate they would have to down-sample to in order to fit the music files on the game disc with the rest of the game’s content. In some cases, if there was an excess of space left, you could even go so far as to leave it as Red Book uncompressed audio that would stream right off of the CD as the game was played. We followed both routes on the “Command & Conquer” series of games, for example, where the main game would use 22k mono WAV files, but the expansions to the games would usually have enough leftover space on the CD to utilize Red Book audio, at least for a handful of tracks.

In Frank’s next installment he’ll continue to discuss the evolution of game music – look for Part 2 next week!

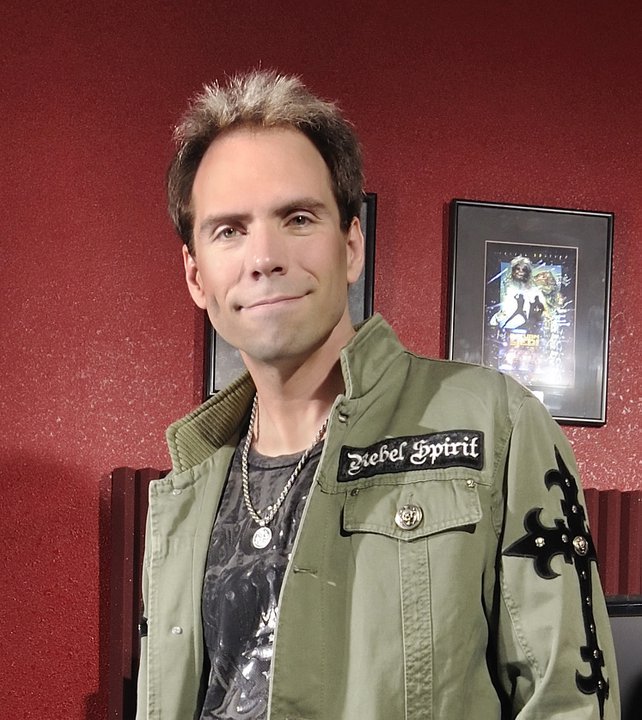

About Frank

Frank Klepacki is an award-winning composer for video games and television for such titles as Command & Conquer, Star Wars: Empire at War, and MMA sports programs such as Ultimate Fighting Championship and Inside MMA. He resides as audio director for Petroglyph, in addition to being a recording artist, touring performer, and producer. For more info, visit www.frankklepacki.com

Follow Frank on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frankklepacki

Follow Frank on Twitter: https://twitter.com/frankklepacki

For the longest time, video game music had a bit of a stigma associated with it – “It’s all a bunch of bleeps and blips.” While the early days of video games – the era of the Atari 2600 – certainly represented that, people fail to realize that games outgrew that more quickly than they think.

In the mid-’80s heyday of arcades, and the release of the Nintendo Entertainment System, the music was using basic FM synthesis such as square waves and saw waves to play back a minimal 4 monophonic channels of music. Even with those limitations, though, some of the games’ music was still very cleverly composed, and remains memorable even today. The “Super Mario Brothers” themes are a prime example of this.

Traditional composers may have dismissed the idea of game music, thinking you couldn’t do all that much with it, or that it wasn’t serious. But as composers who ARE gamers, we understood that it, in fact, forced you to think harder about how you were going to utilize the technology in front of you, and make the most of it. Think about it in terms of having a snare drum, a bass, a flute, and a clarinet – and then being told to compose utilizing only those 4 players/instruments for an entire soundtrack. We accepted the challenge.

In the mid-’80s, the Amiga systems, way ahead of the curve, established sample-based sound capabilities with clever use of RAM to avoid taxing the CPU. By the late ’80s and early ’90s, the next generation of PC sound cards, such as the AdLib and Sound Blaster, became more prominent. Utilizing 11-voice FM synthesis with more customizable instrument capabilities, these sound cards allowed us to do a lot more programming of instrument changes, simulated effects and more sophisticated chord voicings to make the compositions more interesting and dynamic.

Roland also had introduced the MT-32 module, followed by the Sound Canvas, which established the “general MIDI” format, offering higher quality MIDI playback in a pro-sumer synth module that was quickly adopted by the video game industry due to its quality sound palette and ease of programmability. It was popularized in games such as “King’s Quest” and “Monkey Island.” Shortly thereafter, the next generation of consoles, such as the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, were released. Though they shared similar FM synthesis, they also introduced sample-based capabilities. Much like the Amiga, the Super Nintendo allowed use of entirely sampled instruments if you had the RAM available and cleverly allocated it, as we accomplished when I worked on the score for Disney’s “The Lion King” game.

Interestingly, as an alternative during this time, some game composers also used music trackers. Originating on the Amiga to make use of the sampled sounds with sequencing, in the ’90s we started seeing PC versions, most commonly used with Gravis Ultrasound cards, which provided robust hardware mixing that PCs lacked at the time.

During the mid-to-late ’90s sound cards continued to improve. The later Sound Blaster cards offered more sampling and playback options and higher quality sample rates, and the next-generation consoles such as the Sega Saturn and PlayStation were also able to support this. Now music could be heard the way it was composed in the pro-audio capacity, rather than be subject to the limitations of playback of earlier sound cards and consoles. Composers were able to use their synthesizers, real instruments and full band recordings if they wished, the only limitation being the budget they were given, and what sample rate they would have to down-sample to in order to fit the music files on the game disc with the rest of the game’s content. In some cases, if there was an excess of space left, you could even go so far as to leave it as Red Book uncompressed audio that would stream right off of the CD as the game was played. We followed both routes on the “Command & Conquer” series of games, for example, where the main game would use 22k mono WAV files, but the expansions to the games would usually have enough leftover space on the CD to utilize Red Book audio, at least for a handful of tracks.

In Frank’s next installment he’ll continue to discuss the evolution of game music – look for Part 2 next week!

About Frank

Frank Klepacki is an award-winning composer for video games and television for such titles as Command & Conquer, Star Wars: Empire at War, and MMA sports programs such as Ultimate Fighting Championship and Inside MMA. He resides as audio director for Petroglyph, in addition to being a recording artist, touring performer, and producer. For more info, visit www.frankklepacki.com

Follow Frank on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frankklepacki

Follow Frank on Twitter: https://twitter.com/frankklepacki

Published

11th September 2014